FLO MicroCourse: Write your teaching philosophy statement OER

Section outline

-

-

Facilitators: Sue Hellman and Sylvia Currie

Course written and designed by Sue Hellman

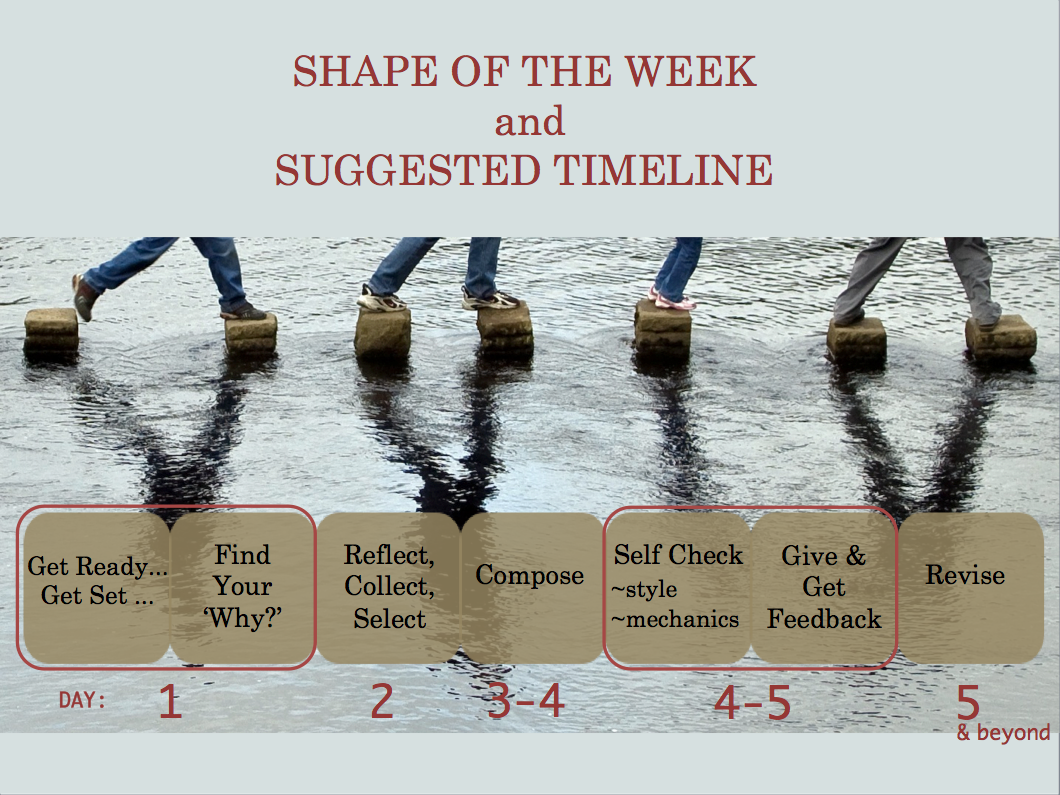

Writing a teaching philosophy statement is a complex task. The volume of 'how to' articles and samples available online can be overwhelming. In this course, you'll find a shortlist of resources organized into a process designed to move you from the initial step of collecting your thoughts to composing a first draft (at least) and receiving peer feedback. You can follow along sequentially or cherry pick topics and activities that best fit your needs.

Writing a teaching philosophy statement is a complex task. The volume of 'how to' articles and samples available online can be overwhelming. In this course, you'll find a shortlist of resources organized into a process designed to move you from the initial step of collecting your thoughts to composing a first draft (at least) and receiving peer feedback. You can follow along sequentially or cherry pick topics and activities that best fit your needs. THANKS to those of you who have already completed the short survey. If you haven't already done so, it's not too late. No names will be made public.

-

What is a teaching philosophy statement (TPS)?

What Makes Good Teaching? A Short Film by Harvard Ed Students

“A teaching philosophy is a self-reflective statement of your beliefs about teaching and learning. In addition to general comments, your teaching philosophy should discuss how you put your beliefs into practice by including concrete examples of what you do or anticipate doing in the classroom.” (U. Minnesota, p.1 PDF)) “Each teaching philosophy statement [also] reflects not only personal beliefs about teaching and learning, but also disciplinary cultures, institutional structures and cultures, and stakeholder expectations as well.” (Schonwetter et al, U of Manitoba & U. of Winnipeg, p.1 PDF)

The most common reasons for writing a TPS are: to apply for a job, a promotion, tenure, or a grant, or to be considered for an award; to complete a teaching dossier; or to take stock and give new direction to your work which “in turn enhances your ability to contribute positively to your learning community.” (Chapnick, Faculty Focus Special Report, 2009, p.4).

What makes writing a TPS so challenging?

If the task this week is causing you some anxiety, you’re in good company. “For most educators, writing a philosophy of teaching statement is a daunting task. Sure they can motivate the most lackadaisical of students, juggle a seemingly endless list of responsibilities, make theory and applications of gas chromatography come alive for students, all the while finding time to offer a few words of encouragement to a homesick freshman. But articulating their teaching philosophy? It’s enough to give even English professors a case of writer’s block.” (Bart, Faculty Focus Special Report, 2009, p.2)

There are several reasons for this:

- There is no standard formula or set of guidelines to follow.

- The writing style -- narrative and first person rather than formal and academic -- is unfamiliar.

- Experienced teachers may have too much to say in 1-2 pages; whereas, new instructors may have too little.

- It can be difficult to show, for example, that you’re passionate, care about your students, take a learner-centred approach, value active learning, and foster individual growth (desirable) without saying that you’re passionate, care about your students, take a learner-centred approach, value active learning, and foster individual growth (undesirable). (Arghh!!!!!)

What will we be doing during the course?

Goals

- To complete a first draft (at least)

- To contribute to a class ‘gallery’ by sharing that draft

- To apply the criteria for an effective TPS when composing and checking your own and reviewing others’ work

- If comfortable, to ask for feedback, specifying what help you need or selecting the rubric to be used

- If time, to revise and share your next iteration

As you work through the steps and take advantage of the support of your colleagues, hopefully you’ll come to think of writing your TPS as an opportunity to indulge in some enjoyable reflection and conversation about teaching plus a little shameless self-promotion :-).

Where to begin?

The articles below, by writers who wrestled in one way or another with TSPs, will get you thinking about different ways to tackle this project.

"How do you write a statement of teaching philosophy that doesn't sound exactly like everybody else's?"

James Lang (2010, Chronicle of Higher Education). 4 steps to a memorable teaching philosophy. From https://www.chronicle.com/article/4-steps-to-a-memorable/124199

"As an academic, I'm used to people paying no attention to what I write. But what about those people who do decide to read my statement? What on earth do they want?"

Jeremy Clay (2007, Chronicle of Higher Education). Everything but the teaching statement. From https://www.chronicle.com/article/Everything-But-the-Teaching/46672/

"Quietly, he read and reread my statement. Then he turned to me and simply said, 'Tell me what you are trying to convey.' I realized I could not succinctly answer his question."

Mary Ann Lewis (n.d., Ohio Wesleyan U.). Teaching statement as self-portrait. From https://chroniclevitae.com/news/734-teaching-statement-as-self-portrait?cid=articlepromo

Why are so few TSP samples provided in this course?

You may be surprised to hear that reading other people's teaching philosophy statements can make finding your own voice and vision more difficult. Drawing on the advice and support of peers and co-workers is more productive. So you decide if you'd find it useful to search online for examples that fit your discipline & exemplify the kind of writing style to which you aspire.

Do I have to follow all the steps?

No, nothing is mandatory. You know best what you need to push forward and achieve your goal(s). According to the pre-course survey, this group is split pretty evenly between those who want to update an earlier TSP and ‘newbies’, so the course has been designed to accommodate both working sequentially and personalizing.