Step 1 Learning Materials

Step 1: Learning Materials

What is a territorial acknowledgement?

A meaningful territorial acknowledgement is an opportunity to situate oneself in personal introductions and to recognize long standing relationships to place. A territorial (or land) acknowledgement is emerging into mainstream educational and professional practice as a way to recognize the historic and current relationships Indigenous Peoples have to the land, water, and natural world. Nuu-chah-nulth educational leader, Asma-na-hi Antoine shares the words of the last remaining fluent Lkwungen language holder who stated, “there was no traditional word for territories, but there was one used for land” therefore with respect for the Lkwungen families, Antoine prefers to use the word land rather than territory (personal communication, 2015).

For Indigenous Peoples, a land acknowledgement is a protocol and practice to respect and recognize the stewardship responsibility and care taking relationship to the lands we visit. A land acknowledgement also includes a cultural introduction to create immediate familial connections. So a land acknowledgement is tied into an introduction of who we are and where we come from. In this Vancouver Island University welcome video, Snuneymuxw Elder, Gary Manson, speaks to the importance of oral protocol when doing a cultural introduction.

Cultural Introductions

While protocols will vary across diverse First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples, some ways to do cultural introductions may include sharing something about our:

- Family connections and/or belonging to nations and places

- Kinship roles, and/or

- Intention and purpose in being in a given place and situation.

The most important thing is to share something about who we are and how we are connected in order to build trust and relationships. As Honorable Justice Senator Murray Sinclair tells us, part of the reconciliation journey is taking responsibility to ensure that all children, regardless of heritage, are able to think about 4 key questions throughout their education: Where do I come from? Where am I going? Why am I here? Who am I? (cited in Sara Anderson, June 9, 2016). You may use these questions to frame your own cultural introduction if you find them helpful. Your facilitators have also shared videos of their own acknowledgments and cultural introductions in the Sharing and Feedback Forum to help you get started.

Was a territorial acknowledgement always done between Indigenous Peoples?

A territorial acknowledgement is a common practice among First Nations in British Columbia due to the diversity of distinct nations across the province. For First Nations that come from large traditional territories such as Cree, a land acknowledgement was not necessary, but a cultural introduction is common practice to locate oneself to family and to build connections with others.

Traditional Indigenous lands vary across Canada from historic treaty lands to unceded traditional First Nations territories. Treaty lands are based on negotiated agreements between the Crown and First Nation communities that were done prior to and after Canadian confederation. There are numbered treaties (1-11), peace and friendship treaties, upper and lower Canada treaties, and modern day treaties. These agreements are still valid today and were established to perpetuate "happy, healthy and vibrant communities" (personal communication, Kevin Lamoureux, 2019).

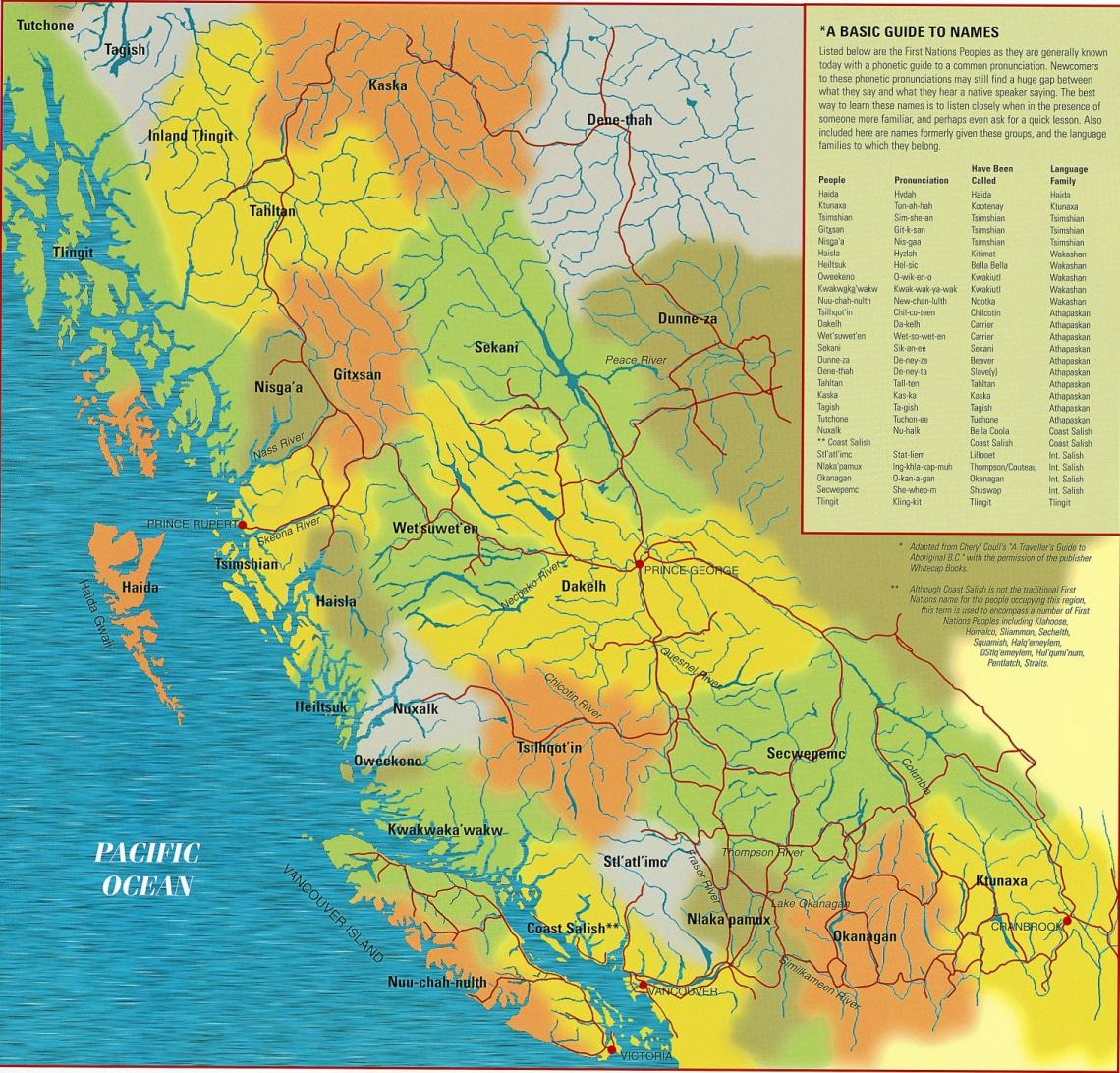

In British Columbia, almost ninety-five percent of the land base is unceded traditional First Nations lands. Unceded means First Nations communities have never surrendered or legally signed away their rights to the Crown or Canada. The following map is a broad representation of First Nation traditional territories in British Columbia. Boundaries are soft as there are shared resources built over time based on familial ties to specific places. Boundaries can also be significant land features such as valleys, rivers and mountains that have family specific creation and transformer stories to explain relationships and responsibilities to the land.

Figure 1: First Nation territories across British Columbia. © British Columbia Ministry of Education.

If you have difficulties seeing the colour spectrum, you can view a similar First Nations of BC map in black and white produced by the Museum of Anthropology in 1994.

Why do we do a land acknowledgement?

"When I was asked why a land acknowledgement is important, I had to reflect on this. As a First Nations person, an acknowledgement always connects me to the Land, announces my intention to those who are stewards and protectors so I can live and work in a 'good way'. For a large part of my life it was dangerous to identify myself as Indigenous because I could be aggressively discriminated against, marginalized, and my contributions diminished. The acknowledgement and cultural introduction establishes who I am, why I am here, and what I hope to do...together. It had nothing to do about asserting rights to a place or disrupting the status quo, an acknowledgement and introduction is how I build a working relationship."

(D. Biin, personal communication, 2019)

Land acknowledgements from settlers and allies began as a form of political disruption and as a way to decolonize spaces where we learn, relate and connect. It has evolved since then. A meaningful acknowledgement re-humanizes and makes 'visible again' the reality that Indigenous Peoples are not part of the past and should be mitigated or forgotten. Indigenous Peoples are still here, contribute to communities, and are re-creating places of healing, recognition and resurgence. A land acknowledgement goes beyond a civil or polite practice and as an act of disruption, it is a way to come together as human beings. As a settler in Canada, a land acknowledgement can be:

- an act of reconciliation and recognition;

- delivered as an act of social justice and mutual respect; and

- a first step when rebuilding relationships.

Beyond this practice, you should be ready to engage in a lifelong learning process. As protocols vary widely between and even within Indigenous cultures, learning how to do an appropriate and meaningful acknowledgement takes time, and requires a relationship. Therefore, it is important to find people who you trust to support you as you learn about protocols. There may be people at your institution who can support this – for example, staff an office of Indigenous affairs or a colleague who has established strong, positive relationships with Indigenous educational partners. The following story highlights how to deepen the learning by exploring the traditional place names.

Place names tour: Promising practice from the University of the Fraser Valley

Knowing traditional place names is important in building relationships with the places we live and teach from. The University of the Fraser Valley (UFV), in partnership with the Stō:lo Nation, has developed a day-long guided tour for staff, administrators, and faculty to take after they have spent time learning about Indigenous-Canadian relationships and history. The place names tour teaches them what is important in the Stō:lo worldview.

Dr. Sonny Naxaxahats’i leads the tour and sets the tone by sharing a key Stō:lo worldview through a greeting stated at the start of an all-Chiefs meeting by Elder Tillie Gutierrez:

S’olh tmexw te ikw’elo. Xolhemet te mekw’stam it kwelat.

(We have to take care of everything that belongs to us).

It reaffirms that Stō:lo People accept responsibility for “everything” living and flowing through the traditional territory.

In the tour, participants learn that some of the English names in the area are translations of the Halq’emeylem names; for example, Chilliwack is Ch-ihl-kway-uhk and Chehalis is Sts’ailes. They also learn that some places describe a geological phenomenon; for instance, Mount Baker is called Kulshan because it refers to the “bleeding wound” at the top of the mountain. (Mount Baker was so named in 1798 by Captain Vancouver. Joseph Baker, Captain Vancouver reported, was the first of his crew, in 1792, to see the mountain). Understanding traditional place names heightens the meaning and relevance of the traditional territory for UFV staff, deepening their relationship to place and peoples. Shirley Ann Hardman (personal communication, 2017) has said, “I like faculty, staff, and administrators to take the Stō:lo place names tour because it provides critical insights into what is valued by the Stō:lo peoples. It helps people to know that there was a whole world here before the farmers, before Costco and the freeway.”

You will need to ask questions and be prepared to make mistakes and apologize if needed. The learning path may not always be smooth, but with practice your knowledge will grow. As an educator, you play a part in modelling and sharing this learning with students. As you build connections with the land, you also build connections with and belonging to Indigenous communities; it enables you to engage with education and community in the classroom, together. Modelling a land acknowledgement with students creates space to talk about systemic change.

What have others done?

Territorial acknowledgements are practiced in many post-secondary institutions across the country. The Canadian Association of University Teachers has developed a living resource called Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory, which shows how institutions are identifying the traditional First Nation, Metis and Inuit lands they conduct business upon.

The person who will be facilitating the gathering or meeting is the person who should acknowledge the lands, and this should be done first and foremost. If you forget to acknowledge the lands immediately then do it as soon as possible. After the acknowledgement you carry on with the agenda. Kwakwaka’wakw educator, Robert Joseph asserts, “For larger conferences, it is good protocol to invite an Elder to provide a prayer or blessing. Again, in order to find an Elder who provides prayers or blessings, call the Friendship Centre [or local Indigenous community] nearest to the location of your event and ask them. Be sure to ask what is the expected honorarium for the blessing” (2013).

Some areas have more than one First Nation in the area and some lands are shared territory. In regard to the Coast Salish peoples, Antoine imparts the teachings from the Royal Roads University Elders Circle and Chief and Council members, who prefer acknowledgments are specific to the families. When Antoine acknowledges traditional lands she does not acknowledge the Coast Salish (larger nation) rather she thanks the Xwsepsum (Esquimalt) and Lkwungen (Songhees) families on who’s traditional lands the university sits (personal communication, 2015).

How do I do a meaningful land acknowledgement?

Some examples of acknowledgments that can be used as a guide to create your own acknowledgement are shown below. Keep in mind these are not the only ways to do an acknowledgment. If your institution or agency has a formal territorial acknowledgement, you can choose to use it for the course activity. The important thing is that whatever words you choose to acknowledge Indigenous lands, use language that is authentic and reflects you, so that it will feel comfortable and natural.Examples:

I would like to thank the ___________________ for agreeing to meet with us today, and for welcoming us to your traditional territory.

I would like to begin our day by acknowledging the ______________________ families and their traditional lands on where we begin our work today. I come from a place of respect and gratitude to know I work, live, and learn in their traditional lands.

I would like to acknowledge that we are on the traditional territory of the _______________ First Nation.

I would like to acknowledge that we are on the traditional territory of the _____________ people.

I would like to acknowledge the ______________ people, whose land we are on.

I want to thank the ________________ people for allowing us to live, learn, and play on their beautiful territory.

We would like to first acknowledge the traditional territory of the _____________ people and extend our appreciation for the opportunity to live and learn on their territory.

As a visitor, I want to acknowledge the traditional territory of the ________________ people, whose land we are meeting on today.

Before going further, I wish to acknowledge the ancestral, traditional and unceded Aboriginal territories of the _____________ (ie. Coast Salish) peoples, and in particular, the _____________________ (ie. Cowichan) on whose territory we stand.

Adapted from:

Allen, B. et al. (2018). "Section 3: Integrate – Ethical Approach and Relational Protocols. Understanding territorial acknowledgement as a respectful relationship". Pulling Together: A guide for teachers and instructors. BCcampus: Victoria. p. 41-42.

Antoine, A. et al. (2018). "Appendix E: Acknowledging traditional lands". Pulling Together: A guide for curriculum developers. BCcampus: Victoria.

Antoine, A. et al. (2018). "Section 3: Engaging with Indigenous Communities. Respecting Protocols". Pulling Together: A guide for curriculum developers. BCcampus: Victoria. p. 30.

Wilson, K. (2018). "Section 1: Introduction to Indigenous Peoples. Acknowledging Traditional Territories". Pulling Together: Foundations Guide. BCcampus: Victoria. p. 22-23.

The complete Pulling Together Learning Series is available at: https://bccampus.ca/projects/indigenization/