Design and Deliver a Rubric

| Site: | SCoPE - BCcampus Learning + Teaching |

| Group: | FLO MicroCourse: Rubrics OER (June 2022) |

| Book: | Design and Deliver a Rubric |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, 14 February 2026, 11:44 AM |

1. Step 1 - Interrogate Goals and Purposes

First, answer this question:What is this assessment task aiming to reveal and measure?

When assessment clearly aligns with outcomes

When designing rubrics, there is a risk that you end up measuring the task itself (e.g. writing an essay, giving an oral presentation), rather than the learning or ability it is supposed to reveal. This is okay if the task is closely aligned to the outcome. Consider these outcomes:

- Students will safely reposition a patient in bed.

- Students will edit and format a document for distribution.

- Students will organize and articulate a written argument.

Choosing an authentic assessment task for each example is fairly obvious - you have the students reposition a patient, format a document, and write an essay. But, what do you put on the rubric? Let's take the first example: Safely reposition a patient in bed.

You need to ask yourself some questions:

- Is this a yes/no competency or are there different degrees of quality of achievement? If so, what is the difference between an outstanding demonstration, a good demonstration, and a merely satisfactory demonstration? What would lead to a fail?

- What if the students need to ask you questions during the demonstration?

- What if they do something incorrectly or make a mistake, but can tell you what they did wrong?

- Do they need to complete the demonstration under pressure (like on practicum or in an exam setting), or can they do it at home with a family member and video it?

- How many times do they need to demonstrate correct repositioning to be considered proficient?

Let's examine another outcome: Students will organize and articulate a written argument.

You have them submit an essay. But what goes on the rubric? Ask yourself a few key questions, such as:

- What course is this - Introduction to College Writing, Communications, or upper level Political Theory? Context matters when it comes to building a rubric. This is why you can't just find a general essay-writing rubric off the internet!! The level and focus of the course will impact how you build the rubric.

- What is most important - evidence that students have conducted research, clear sentences, organized ideas, whether the argument is convincible, correct formatting of references and layout, or evidence that the student "knows" a lot about the topic? The trouble is that in many cases, such as this one (an essay), the task can't easily be reduced down to independent component parts. For example, clear sentences and the organization of ideas influence the strength of the argument, so if you score poorly on one, you are likely to score poorly on the other. When you break a task apart, you can't help but end up with unfair redundancies in the rubric. This is likely something you'll need to consider.

- Do they need to write the essay under exam conditions or can they write it over time at home?

- What if they don't complete the essay, but submit a detailed, correctly formatted annotated bibliography and an outline of a convincing argument, presented as a set of well reasoning bullet points?

These questions are best considered collaboratively - with your fellow instructors, and with your students. This level of interrogation, if done up front, will make rubric-building smoother, even for straight-forward, well-aligned assessments.

When assessment doesn't closely align with outcomes

Not all outcomes are quite as easily demonstrable as the ones given above. In this case, you need put assessment tasks in front of students that aim to reveal, hint at, or suggest they have met the outcomes. Consider these outcomes:

- Students will demonstrate understanding of the impact the Indian Act has on unceded territory in BC.

- Students will work cooperatively and act with professionalism.

- Students will develop appreciation of literature and literary movements.

Ask yourself these questions:

What task (or set of tasks) will reliably reveal achievement of each of these outcomes? Does every student need to do the same task, or are there multiple ways to demonstrate achievement? How might you break apart "understanding", "cooperation and professionalism", and "appreciation" (from the examples above) into observable criteria? The answers to these questions will not only help you design an effective assessment task, but they will also guide your decisions around what criteria to put on the rubric.

KEY TAKEAWAY - Before you launch into the rubric design, interrogate the goals and purposes of your assessment tasks.

2. Step 2 - Pick your Rubric

You now need to choose a rubric. Refer to the book chapter "This and That" in the previous phase to learn about the different kinds of rubrics.

- Are you primarily using the rubric to score performance fairly, like a cheat-sheet for yourself? If so, choose a holistic rubric or a simple marking guide.

- Are you hoping to provide guidance to students about what constitutes quality performance in advance of them completing the task? A analytical rubric might be better.

- Do you want to design a frame for giving feedback? Perhaps a single-point rubric is the best choice.

Identifying your intention will help you decide which rubric to choose. You could also ask your students what kind would serve them and their learning best.

3. Step 3 - Identify your Criteria

This is where you put to use the time you invested in Step 1. Don't trivialize the work students do by breaking it into too many parts - three to four criteria is best. Choose criteria that align with your outcomes and the goals you identified in Step 1. Look for those pesky redundancies and invalid weightings. For example, unless the essay task is being given to graphic design students, "formatting" should not be equally weighted with "clearly supported argument." At this point you are using your expertise and professionalism to make judgments about what is most important, so it's a good idea to share your thinking with colleagues.

To help guide the selection of your criteria, go back to your outcomes to see what is specifically being assessed with this task. For example, if your outcome is: "Learners can reliably demonstrate how to use de-escalation techniques to neutralize conflicts", you might give them a set of scenarios to analyze and create if-then statements. This could serve as the first of a few increasingly more complex and targeted assessments of the outcome. After completing the interrogation in step 1, you might choose the following three criteria:

- Analysis indicates understanding of situation

- Phrasing of verbal interventions likely to de-escalate

- A range of possible reactions are given

Often criteria are titled with a noun, such as "Analysis", but it's helpful, at this planning stage, to write them as a statement of expected performance, like the examples above. This will give you a head start when it comes to writing the descriptors. It would also help if you can list some actual things you are looking for to decide if they have met those criteria. For example, for the second criterion (phrasing of verbal interventions), you might list some examples. And for the third criterion, starting thinking about how many examples would constitute an acceptable "range". In this way, you are well on your way to "showing" what quality is rather than just telling.

Write down three to four demonstrable, high-value criteria on your page and list some examples that might show what you mean. Don't put them into a table just yet.

4. Step 4 - Discuss Quality

How many delineations of quality can you reliably distinguish for each of your criteria? It's important to note that instrument reliability decreases with number of delineations. Also, you actually start using norm-referencing to make your judgements if you have too many, which leads to conversations with yourself that go something like this: "I don't know what makes it a 6/10 essay introduction, except for the fact it's not quite as good as the one I gave a 7/10".

Not all criteria need to have the same number of delineations. Many criteria are best measured as a yes/no, whereas some criteria could be performed at an expert, excellent, satisfactory, or not-yet level.

If your institution assigns letter grades, you might think about some criteria (or the entire performance) along an A-F grading system. Can you clearly describe the difference between an A, B, C, D, and F essay, oral presentation, reflection, or portfolio?

Many criteria cannot be described as discrete levels of performance and are more like a sliding scale of developing competency. This is important to think about before creating your rubric. For example, do you know when a "Satisfactory" becomes a "Proficient"?

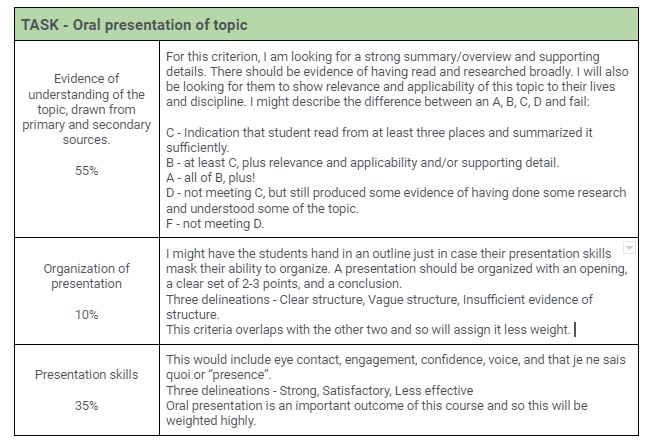

Write out some notes about each criteria that include descriptions of the range of quality you might see, considerations, and rationale. See below for an example of some notes I've made to myself in advance of building a rubric for an oral presentation.

5. Step 5 - Build the Rubric

It's now time to start turning your notes into a presentable format that can be pasted onto an assignment brief, and/or built into the learning management system. But note, a rubric DOES NOT have to be presented in a table!! Also, consider if you could show what each level of quality means, rather than describe it in words. "Exemplar rubrics" are immensely powerful for student learning, and there's a fun example of one in the PPT file - Example Rubrics (found in the next phase)

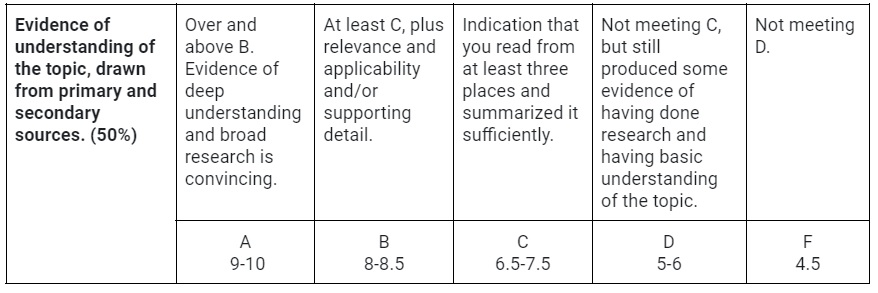

Let's consider the oral presentation example provided in the previous chapter. Here is how one might lay out the description for the first criterion.

Your turn: Take at least one of your criteria and describe each delineation of quality or level of success. Be careful using "hedge words" such as good, very good, excellent, unless it is clear to the students what the difference is between them.

6. Step 6 - Scoring

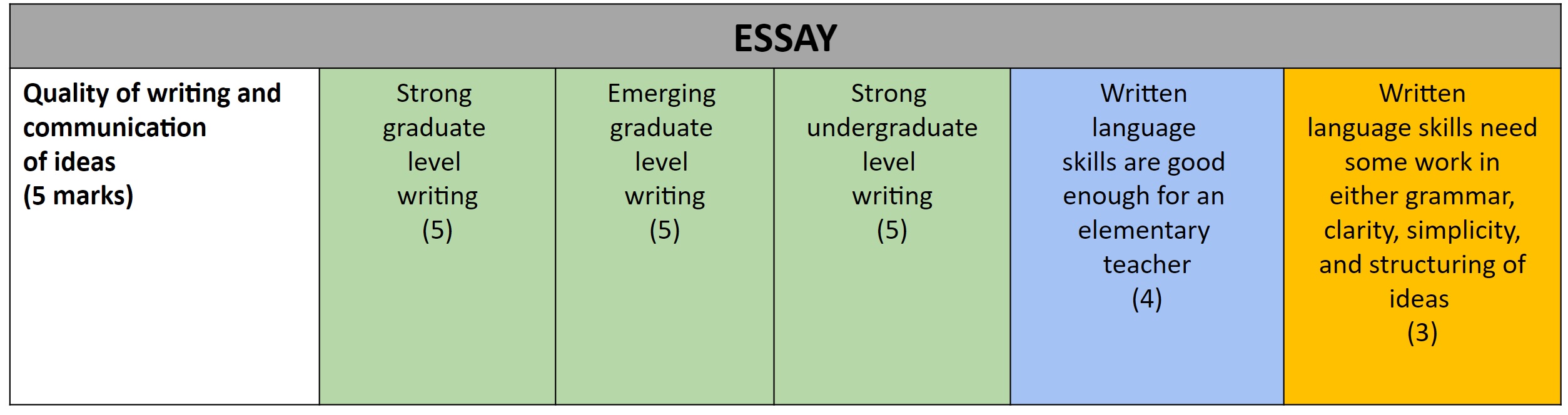

If you're using the rubric to score student work or performance, it's important to consider a few things as you assign the numerical labels:- Consider the ceiling. Does your rubric need to numerically distinguish between meeting the outcomes, meeting them with excellence, and exceeding them? What are the scoring implications? A student who has met the outcomes should surely get full marks, but what about one who performs over and above? Here is an example of a rubric that takes this into consideration. It was created for an essay assigned to upper level students doing an undergraduate degree in elementary education. You can see how it shows students that even though their level of work might be sufficient for full marks in this context, there is still room to improve. To boost the effectiveness of this rubric as a tool for learning and improvement, one would add a feedback or comment line that lists a few examples of what, specifically, would take it to the next level.

- How many degrees of failure do you need to indicate? It's okay to have the minimum score for passing the course be the lowest score possible on the rubric. In the example above, 3/5 is the lowest score you can receive for quality of writing. There is no need to distinguish between a 60% level of writing, which in this program was considered not-good-enough, and a 40% (even more not-good-enough?).

- Check to see if your "rubric algorithm" will garner an overall score that aligns with the descriptions. For example, if you have a column labeled with some version of "Very Good" and the students receive checkmarks all the way down that column, then their overall score should reflect "Very Good". If the rubric "machine" spits out a 65% at the end, then you're scoring will need to be adjusted.

7. Step 7 - Involve students

Rubrics take a lot of work to build and so you want them to be effective tools for both you and the students. How do you get students to read them, understand them, and use them as a tool for learning and improvement?

Here are a few tips to consider:

- Ask students to submit the rubric with their assignment, completed with a self-evaluation.

- Give students a sample of work from previous years or courses and have them practice using the using the rubric to judge work.

- Provide written feedback before a score on a rubric (see Butler article in resources section).

- Have students contribute to building the rubric.

- Lead a conversation about each criteria and what is meant by the different levels of success.

8. Final Word

There is no objectively "correct" or "perfect" rubric. Rubrics are only as good as they are useful to you and your learners. As you use your rubric for the first time on a sample of work, you'll quickly determine how effective it is for the purposes it was intended.Rubrics constantly need checking, tweaking, and sometimes completely rebuilding so don't worry if the first one you build needs improvement. After you've finished marking a set of assignments or performances, reflect on the following questions:

- Did this rubric make my evaluative judgment more reliable, accurate, and efficient?

- Do I feel like the rubric fairly treated the range of performances?

- Is there evidence that the students used the rubric to either guide their work in advance of their submission and/or reflect on what their performance afterwards.

- Is there a colleague I could discuss this with to get insight and feedback on how it went?

- Do all the users understand the descriptions and overall expectations the same way? Did you get any questions of clarification or push-back from your students about their score?

- What changes can I make to improve it for next time?