Week 2: Overview

| Site: | SCoPE - BCcampus Learning + Teaching |

| Group: | Facilitating Learning Online - Design NOV2017-OER |

| Book: | Week 2: Overview |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, 14 February 2026, 4:44 PM |

Description

a quick review of learning theories, instructional design approachs and related concepts/ideas to help ground each design plan.

How do people learn

There are many theories about how people learn - unfortunately we don't have time to explore each one. If you haven't had a chance to explore learning theories before, or it has been a while, you can refresh your knowledge by reviewing the next page: Learning Theories - Review.

Design for online learning

The focus in this workshop is on designing a short unit of online learning. We'll discuss different challenges and benefits you need to consider when you're designing for diverse learners. There are many different approaches to instructional (learning) design. You can browse a Prezi overview - Design for Learning - of some of the learning and instructional design ideas we'll look at throughout FLO-Design workshop. The remaining pages in this book contain more details and three potential approaches you can select to begin your own design project.

Explore stories of design (Explainers)

If you're new to instructional or learning design, or you're just seeking inspiration, we'll take time to share some stories and examples of different courses and workshops. We encourage you to share ideas, questions and examples - the collection of examples can "spark" greater creativity and innovation for all of us.

Select an Instructional Design Approach

Take time to review the three potential instructional (learning) design approaches in this book. You should choose one approach to guide your design project for this workshop.

Learning Theories - Review

Learning theories present ideas about the way that people learn; some theories derive from critical analysis, research and a significant body of evidence from testing in various educational situations. You may also notice that some widely accepted theories lack substantive research but are still valued by many experienced educators as they reflect some shared experiences with students and can still provide valuable guidance in developing courses.

Learning theories do not provide clearcut answers about the best ways to design learning for our increasingly complex and diverse society but exploring some of the philosophical foundations and critical elements of each major group of theories can be helpful in developing more flexible, varied approaches to education. You do not need to become an expert on learning theories to be a successful designer but an awareness of the theoretical foundation for many of the current course and curriculum designs can be helpful.

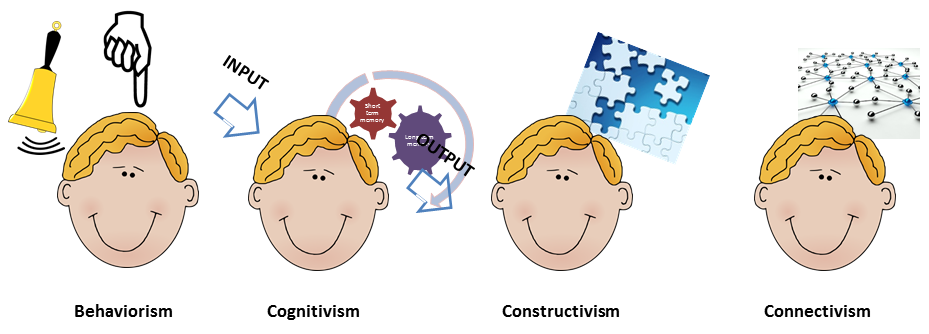

A simple way to organize your understanding of traditional and developing learning theories is to consider the four categories below: Behaviourism, Cognitivism, Constructivism and Connectivism. The titles reflect a shared focus and perspective on human learning and the nature of knowledge and reality.

Behaviourism includes theories that are based on changes in behaviour that can be directly observed and measured. Cognitivism includes theories that focus on the way the human brain take in information and stores it for recall and application. Constructivism includes a range of theories that begin from a subjective perception of reality and may include a belief that learning occurs through social interactions. A final theory (still argued by many) is Connectivism. This theory was developed to address the way learning has changed due to the exponential increase in information due to advances in digital technologies and connectivity. A central belief is that learning occurs primarily (most effectively?) through networked learning.

Some of the important questions you may ask about each are included in the table, followed by the names of some of the leading theorists.

| Behaviourism | Cognitivism | Constructivism | Connectivism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How does learning occur? | stimulus -> response; observable behaviour main focus, chaining events | input -> process -> output (learning) structured, computational | meaning created by each learner (personal);focus on social learning | Distributed within a network, social, technologically enhanced, recognizing and interpreting patterns |

| What factors influence learning? | nature of stimulus (reward; punish), timing of events | existing schema, previous experiences | Engagement, participation, social, cultural | Diversity of network |

| What is the role of the memory | Repeated experiences are remembered - timing & type of reward / punishment are most influential | Encoding to long term memory, retrieval | Prior knowledge remixed to current context | Adaptive patterns, representative of current state, existing in networks |

| How does transfer occur? | Stimulus, response | Duplicating knowledge constructs of "knower" | Socialization | Connecting to (adding nodes) |

|

What types of learning are best explained by this theory? |

Task-based learning | Reasoning, clear objectives, problem solving | Social, vague ("ill defined") problem solving | Complex learning, rapid changing core, diverse knowledge sources |

|

Names of some theorists |

I. Pavlov, B.F. Skinner, J. Watson | D. Ausubel, J. Bruner, R. Gagne | J. Dewey, L. Vygotsky, E. von Glaserfeld | S. Downes & G. Siemens |

You may also enjoy exploring the amazingly comprehensive and interactive learning theories map, created by Richard Millwood for a European Union project: HoTEL (Holistic Approach to Technology Enhanced Learning).

References

Fredholm, Lotta (2001) Ivan Petrovich Pavlov (1849-1936). Nobelprize.org. Retrieved from https://www.nobelprize.org/educational/medicine/pavlov/readmore.html

Greengrass, M. (2004) 100 Years of B.F. Skinner, American Psychological Association. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/monitor/mar04/skinner.aspx

HLWiki Canada. (2016) John Dewey, Creative Commons BY-NC-SA, Retrieved from http://hlwiki.slais.ubc.ca/index.php/John_Dewey

HLWiki Canada. (2015) Gagne's Nine Events of Instruction, Creative Commons BY-NC-SA, Retrieved from http://hlwiki.slais.ubc.ca/index.php/Gagne's_Nine_Events_of_Instruction

HLWiki Canada. (2015) Lev Vygotsky, Creative Commons BY-NC-SA, Retrieved from http://hlwiki.slais.ubc.ca/index.php/Lev_Vygotsky

Siemens, George (2005) Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age, International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning. Retrieved from http://www.itdl.org/journal/jan_05/article01.htm

Smith, M.K. (2002) ‘Jerome S. Bruner and the process of education’, the encyclopedia of informal education. [http://infed.org/mobi/jerome-bruner-and-the-process-of-education/ Retrieved: Dec. 10, 2016]

Smith, M. K. (2003). ‘Learning theory’, the encyclopedia of informal education. [http://infed.org/mobi/learning-theory-models-product-and-process/. Retrieved: Dec. 10, 2016].

Millwood, Richard. (2013) Learning Theory, v6, Holistic Approach to Technology Enhanced Learning (EU-funded project), retrieved from http://hotel-project.eu/sites/default/files/Learning_Theory_v6_web/Learning%20Theory.html

Scientific Reasoning Research Institute. von Glasersfeld, Ernst. Radical Constructivism. Retrieved from https://www.srri.umass.edu/vonglasersfeld/

Weibell, C. J. (2011). Principles of learning: 7 principles to guide personalized, student-centered learning in the technology-enhanced, blended learning environment. Retrieved Nov. 4, 2016 from [https://principlesoflearning.wordpress.com].

Wikipedia article - David Ausubel - Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Ausubel

Instructional Design Approaches

Instructional design is a systematic approach to creating curriculum and courses, using learning and instructional theory. While most of the well-known (and widely used) approaches are not explicitly for online course design, they are still useful when thinking about designing your learning units for this workshop.

Starting from ADDIE

The most commonly used instructional design approach is the "ADDIE" model. An instructional design approach developed for the U.S. Army in the mid-1970's, this model is made up of five phases:

- Analysis

- Design

- Development

- Implementation

- Evaluation.

Although it has been criticized as restrictive and linear, it can be interpreted and applied in a wide variety of educational contexts and has proven to be flexible in application. For a further discussion of the benefits and limitations of the model, see section 4.3 The ADDIE model from "Teaching in a Digital Age" by A.W. Bates.

Current adaptations of the ADDIE model often include some form of rapid prototyping of course or program elements. Rapid prototyping is a product or software development approach that has been integrated into educational design to make the process more efficient and adaptive. By testing a component of a course design before the entire design is complete, design flaws or misunderstandings can be caught early in the process, thus saving time and resources.

Another attempt to make course design approaches more flexible was the development of agile design models. Agile design generally involves smaller groups, often only two people, who access other experts as required during the design process (Bates, 2015). In recognition of the emergent nature of knowledge and the changing needs of diverse learners, the content is flexible and adapts to changing tools and educational technologies as they become available. An example of agile instructional design is SAM - Successive Approximation Model.

Instructional design models vary in terms of their emphasis on the process, the products and the learning / learners. Some academic environments use a new term, "learning design" to emphasize the focus on the learner and the outcomes of the learning. The term "instructional design" is seen as representing a focus on teaching and a "transmission" of knowledge model of learning. Other educators seem to use the terms interchangeably. The important thing is for you to be aware of the perspectives you feel are most representative of your own values and those of your institution.

Instructional Design Approaches

For the purpose of this FLO-Design workshop, we're suggesting you consider one of three guiding approaches to your design project. Each of the three approaches can integrate the basic elements of ADDIE and prototyping to develop a more comprehensive design plan. You could consider:

Approach 1. a traditional (well-tested) Outcomes-based Approach;

Approach 2. a "Design Thinking" Approach; or

Approach 3. an "Open Practices" Approach.

These three approaches are described in the following pages.

References

1. Outcomes-based Learning

In the past, an instructor would be assigned to teach a course and focused first on selecting a textbook and identifying the major topics and concepts that needed to be covered. This often resulted in content-based, transmission model of delivery courses.

Most course outlines in higher education now include learning outcomes (although some still use the language of "objectives") and course design has become "outcomes-based".

An associated concept articulated by John Biggs, an Australian-born professor and writer, referred to the value of making the assessment and teaching strategies coherent with the stated outcomes; this concept is known as "constructive alignment."

An "aligned" curriculum is developed from intended learning outcomes, followed by logically connected learning/teaching activities and assessments (including formative and summative or evaluative instruments). The design process is not linear but an integrated flow that is always measured against the intended outcomes for learners.

This outcomes-based approach is expanded and applied, in many higher education institutions using two well-known approaches to course design:

- Understanding by Design by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe provides an outcomes-based approach often referred to as "backwards" design. The UbD framework integrates a focus on the "big" questions or concepts that help an instructor develop curriculum that leads to deeper student understanding and achievement. While design still begins from a focus on the learner, the UbD framework helps designers overcome the perceived limitations of focusing on content or outcome statements alone.

- Integrated Course Design, by Dee Fink focuses on a design process to create "significant learning experiences" for students. His approach involves a unique Taxonomy of Instructional Goals and an Integrated Design Process

You may choose some variation of the outcomes-based approach to learning design. Further sample checklists and links to design tools will be shared during Week 2

References:

Culatta, R. (2015) Transformative Learning (Jack Mezirow) Instructional Design.org. Retrieved from http://www.instructionaldesign.org/theories/transformative-learning.html

Fink, L. Dee (2005). A Self-Directed Guide to Designing Courses for Significant Learning (pdf), Dee Fink & Associates. Retrieved from https://www.deefinkandassociates.com/GuidetoCourseDesignAug05.pdf

Smith, M.K. (2002) 'Malcolm Knowles, informal adult education, self-direction and andragogy', the encyclopedia of informal education, http://infed.org/mobi/malcolm-knowles-informal-adult-education-self-direction-and-andragogy/

University of Alaska Fairbanks, eLearning & Distance Education, iTeachU, Pedagogy Resources: Backward Design, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, Retrieved Nov 2017 from https://iteachu.uaf.edu/backwardsdesign/

University of Athabasca, Community of Inquiry Model (website). Retrieved from https://coi.athabascau.ca/coi-model/

University College Dublin Teaching and Learning, Using Biggs' Model of Constructive Alignment in Curriculum Design, Becoming a Better University Teacher, Creative Commons 3.0 Unported License. Retrieved from http://www.ucdoer.ie/index.php/Using_Biggs'_Model_of_Constructive_Alignment_in_Curriculum_Design/Introduction

Additional references:

Fallahi, Carolyn (2011) Using Fink's Taxonomy in Course Design, Association for Psychological Science

2. Design Thinking for Education

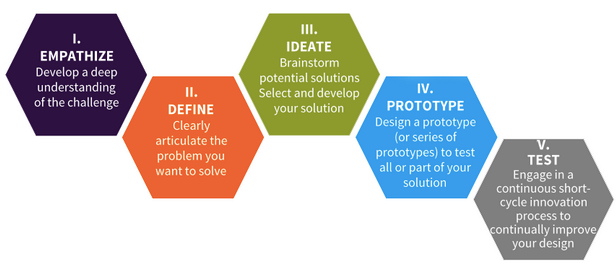

"Design thinking" is a human-centred design approach that was popularized by IDEO, an international design company. The higher education world began to explore how this design approach could enhance their approaches to curriculum design and development and it is now a recognized alternative to curriculum design. The central focus - understanding the needs of people - is similar to outcomes-based approaches but the process is more open and fluid. Other important aspects of the model are its focus on posing "good" questions, reviewing a wide range of conflicting ideas, innovation, and repeated cycles of testing and improvement (sounds familiar?)

The 5 phases model begins from:

Empathy: designers take time to reflect on the people that are their audience and purpose. You may find it useful to view a short video about empathy by Brene Brown (see below). Some versions of Design Thinking develop detailed descriptions of learners called "personas" to guide their designs.

Define: frame the problem and purpose clearly - why are you doing this?

Ideate: a guided brainstorming step that seeks to draw out as many ideas as possible. Finding innovative ideas is a goal of this step in the process.

Prototype: after selecting the main ideas, this step involves "fleshing out" the ideas and providing detailed models or illustrations of how they would work in practice. The purpose is to share the ideas to gather feedback and test the assumptions and beliefs that underly each idea.

Test: the final step is to test the ideas - build your prototype and try it out on sample audiences or in a real context. Collect responses and ideas for what worked and what didn't - return to the design cycle to integrate what you've learned.

You can explore some examples of how each phase occurred in Using Design Thinking in Higher Education or visit an application of design thinking Rethinking Your Course, in a recent project at University of Guadalajara (UdG), led by Justice Institute's Tannis Morgan.

References

Brown, Brene (2013)

Morris, Holly and Greg Warman (2015) Using Design Thinking in Higher Education, EDUCAUSE Review, Jan. 12, 2015. Retrieved from http://er.educause.edu/articles/2015/1/using-design-thinking-in-higher-education

IDEO's Design Thinking Toolkit for Educators, Retrieved from https://www.ideo.com/us/post/design-thinking-for-educators

Thompson, Gary (2010) Personas, FLUID Project wiki https://wiki.fluidproject.org/display/fluid/Fluid+Project+Wiki

Stanford's d.school Virtual Crash Course in Design Thinking. Retrieved from http://dschool.stanford.edu/dgift/

3. Open Education

The concept of "open education" is an evolving approach that currently includes a wide continuum from using open educational resources (OERs) to "build" your course (that you continue to design with an overriding traditional approach) to designing courses that integrate open teaching practices, open co-creation of learning activities and artifacts, and resharing into the open community.

A straightforward "open" approach to course design is the "5R Open Course Design Framework." David Wiley has been a long-time leader in the field of "open" and his "5Rs" approach (i.e., Retain, Reuse, Revise, Remix, Redistribute) emphasizes a change in thinking in design and teaching practices. While his approach still follows traditional design practices (such as Mager's Audience-Behavior-Condition-Degree method for writing learning objectives and constructive alignment of course elements) his "open" approach emphasizes an "authentic" learning perspective in designing "renewable assignments", involving students in reviewing, re-organizing and improving course materials, and encouraging students to "share back" by open-licensing their creations.

Wiley's explanation of his "5R Approach" also touches on designing outside of the traditional LMS - similar to the Flipped LMS approaches shared by BC's Paul Hibbitts. Hibbitts also design and develops his courses in the open; a case study he presented at an ETUG workshop in 2014 includes slides of the weekly resources and information he shared through social media channels while developing his User Interface Design Course.

Open design courses may follow a connectivist or network-theory approach to learning. Some well-known examples of completely open, online, connected courses are:

- ds106 Digital Storytelling, an open, online course from University of Mary Washington. First run "open" in 2012.

- #PHONAR, a free and open undergraduate photography course. runs periodically, open structure and resources to view

- Connected Courses: Active Co-Learning in Higher Ed, a self-paced yet collaborative model of open design intended to "provide educational offerings that make high quality, meaningful, and socially connected learning available to everyone. Offered Sept-Dec 2014 - structures and resources still available for use.

A final example of open educational design is develop

To learn more about finding OERs or ideas for "open learning design"

Take a few minutes to read a 2016 overview from BCcampus "The Canada OER Group: Saving students money from coast to coast." The article identifies Canadian leaders in open practices and links to various collections of OERs and open textbooks. Stories of teaching in the open and guides to finding various OERs can be explored on the Open UBC site. You can also go to the Creative Commons site: Education / OER to find various US-based repositories or organizations such as OER Commons

References

BCcampus OpenEd (2016). The Canada OER Group: Saving students money from coast to coast, news posting Jun 29, 2016.

Open UBC, What is teaching in the open? Teach - see also Open resources, Open assignments, Open practice, Resources (accordions following the main article) - Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

Creative Commons, Education / OER website, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

OER Commons, Open Educational Resources, by Subject, by Grade Levels, by Materials Types, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License

David Wiley, (2015) 5R Open Course Design Framework, Fall 2015 Version, Slideshare, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

CUSO Professional Education, (2014) The ABCD Method of Writing Measurable Objectives (pdf)

Hibbitts, Paul (2015) Flipped-LMS Approach Using an Open and Collaborative Web Platform, blog post December 18, 2015, Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike License (on Github)

Hibbitts, Paul (2014) Developing a course in the open: a case study, on SLIDES, presented at ETUG Spring Workshop 2014

Active Learning

As instructors and designers, we've moved from traditional approaches to transmitting knowledge through expert lectures, and asking students to demonstrate their learning through written papers and mid-term and final exams. Active learning is a teaching method or approach that strives to involve students in learning to achieve more than short-term retention of information. Students are asked to read, write, discuss or solve problems and engage in more complex levels of learning that involve analysis, synthesis and creativity.

Active learning strategies in online course design are important in keeping a student "connected" to the online learning environment and help them to succeed in achieving the outcomes of a course. We'll explore active online learning activities in greater detail in Week 3, as you begin to develop your prototype online learning activity.

When designing for active learning online, keep in mind the Community of Inquiry model and the changing roles of instructor and learners (i.e., instructor becomes more of an guide and facilitator of learning through cognitive and social interactions, and the students take on more responsibility for their own learning and contributing to the online learning community). A related area of research is Terry Anderson' Interaction Equivalency Theory that identifies three important types of interaction between

- students and content;

- teacher and students

- students

Further research by Robert Bernard and colleages (2004) indicated that increasing any of the three types of interactions increased student performance.

While the role of the instructor is still critical in scaffolding deeper learning online, designing a variety of activities, that involve the learner in self-directed and collaborative activities is an effective design strategy. Some key elements to keep in mind:

- offer different types of interactive activities

- build sequential activities in which each builds on the preceding one

- provide timely constructive feedback, from the instructor and from peers

- allow time for reflection and assessment of learning progress

While much of the current course design and development in higher education follows a constructivist model, the evolving "new" learning theories like connectivism, and related concepts of networked learning and "21st century learning", rely on creating safe learning environments and enabling or supporting learners to explore and create learning with peers.

Learning takes place between instructors, students and content in the online "classroom" and beyond as students increasingly seek out meaningful learning through personal learning networks and social media platforms.

References

Anderson, T. (2010). Interactions Affording Distance Science Education. In D. Kennepohl & L. Shaw (Eds.), Accessible Elements: Teaching Science Online and at a Distance (pp. 1-18). Edmonton: Athabasca University Press.(p10) Retrieved from http://www.aupress.ca/books/120162/ebook/01_Kennepohl_Shaw_2010-Accessible_Elements.pdf

Guides for Design

As more and more higher education institutions have moved courses online (either fully online or blended/flexible delivery) there has been an increasing interest in developing a consistency and quality of learning experience for students. Some institutions develop "quality" standards or best practices guidelines that are used to evaluate and improve online courses; others provide rubrics or frameworks to guide the design and development from the start. A general framework to guide your design project is Chickering and Gamsons" "Seven Principles of Good Practice in Undergraduate Education". A time-tested approach to student success, it can also be applied to online learning.

You might consider whether your design will :

1. Encourage contact between students and faculty.

2. Develop reciprocity and cooperation among students

3. Encourage active learning.

4. Give prompt feedback

5. Emphasize time on task.

6. Communicate high expectations

7. Respect diverse talents and ways of learning.

Similar principles are cited in other guidelines.The University of Mary Washginton's Online Learning Intiative uses five principles to guide their online learning designs (cited in Inside Higher Education article, 2012) :

- Develop a learning community

- Provide a high degree of interactivity - between instructors and students and among/between students;

- Provide active learning

- Encourage reflection

- Include opportunities for self-directed learning

And a recent multi-case study analysis of student perceptions of the important factors of online course design (Fayer, 2014) identified the most valued elements as those related to the instructor's knowledge and instructional skills online and on the design of the course:

Strong Course Organization

- provide highly organized course materials / documents prior to the start of a course

- allow students to access all content modules at start of course so they can explore and manage their time

- provide multiple opportunities to engage with complex content and master important concepts

- provide structured and timely feedback

- ensure relevance of content and activities is clear to students

For examples of popular quality guidelines, see the following page.

References

Crews, Tena B., et al (2015) Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education: Effective Online Course Design to Assist Students' Success, Merlot Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, Vol.11, No.1, March 2015. Retrieved from http://jolt.merlot.org/vol11no1/Crews_0315.pdf

Dreon, Oliver. (2013) Applying the Seven Principles for Good Practice to the Online Classroom, Faculty Focus, February 25, 2013, Retrieved from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/online-education/applying-the-seven-principles-for-good-practice-to-the-online-classroom/

Fayer, Liz (2014) A Multi-Case Study of Student Perceptions of Online Course Design Elements and Success, International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, Vol 8, No. 1, Article 13, Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=ij-sotl

Kim, Joshua, (2012) 5 Foundational Principles for Course Design, Inside Higher Education, Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/5-foundational-principles-course-design

University of Florida, Center for Instructional Technology and Training (2016) Chickering and Gamson 7 Rules for Undergraduate Education, Retrieved from http://citt.ufl.edu/tools/chickering-and-gamson-7-rules-for-undergraduate-education/